The PA Backyard Fruit Growers held their annual fruit tree grafting workshop last weekend. There were apples, pears, kiwis, grapes, and even a few berries available for grafting or propagation.

And of course the varieties offered were rare, antique, and unusual cultivars that are grown and maintained in the orchards and backyards of the organization’s members. It was a great opportunity to expand a fruit tree collection, or as in my case, to learn the tricks of crafting a fruit tree from two slender twigs.

Pros and Cons of Grafting Fruit Trees for the Backyard Garden

Grafting is the practice of uniting a scion (the fruiting wood) to a rootstock (base and roots) to create a tree that will grow to the desired size and bear the fruit of your choice. If you’ve purchased a fruit tree from a nursery all this work has been taken care of for you already.

Grafting is the practice of uniting a scion (the fruiting wood) to a rootstock (base and roots) to create a tree that will grow to the desired size and bear the fruit of your choice. If you’ve purchased a fruit tree from a nursery all this work has been taken care of for you already.

The advantages of grafting your own fruit trees include the fact that it’s a lot more economical than purchasing grafted trees. Also, the grafting process is relatively easy to do, and it gives you total control over the varieties of fruit and the size at maturity of the trees that you plant in your backyard.

On the downside, grafting may result in longer wait before you taste your first fruits since trees purchased from the nursery will be older and further along. Also there’s no guarantee that a graft will take, especially if you are just learning the process. Care is required as there is knife work required to cut, notch, and splice the end of the scion wood to the rootstock.

Scion Wood for Use in Grafting Antique Fruit Trees

The scion wood available for grafting at the workshop was all contributed by BYFG members from prunings that were recently cut from mature fruit trees. There were over fifty antique apple varieties, and a smaller number of pear scion wood on hand for participants to select from.

The scion wood available for grafting at the workshop was all contributed by BYFG members from prunings that were recently cut from mature fruit trees. There were over fifty antique apple varieties, and a smaller number of pear scion wood on hand for participants to select from.

The scion wood looked like ordinary tree trimmings that you could find lying around the lawn. Most were the thickness of a pencil or slightly thinner and up to a foot in length. In theory all you need is a small section of fruiting wood with a couple of live buds to perform a successful graft.

There are advanced techniques and varying preferences for grafting fruit trees but during the workshop we were using a pretty basic whip and tongue graft to mate the scionwood to the rootstock. Skills such as interstem grafting or grafting multiple varieties onto a single tree weren’t covered but once you get the basic technique down there’s no limit to the types of grafts that can be experimented with.

Rootstocks; Starting a Fruit Tree on a Good Foundation

If you ever hear a group of apple growers tossing around strange combinations of letters and numbers, they are talking rootstocks… M 27, ELMA 26, BUD 9, GENEVA 30, and MM 111 are just a few of the common rootstocks used to graft fruit trees.

If you ever hear a group of apple growers tossing around strange combinations of letters and numbers, they are talking rootstocks… M 27, ELMA 26, BUD 9, GENEVA 30, and MM 111 are just a few of the common rootstocks used to graft fruit trees.

Selection of the appropriate rootstock is very important as it will determine the ultimate size, vigor, and height of the mature grafted tree. The rootstock can maintain a tree at a dwarf size that can be harvested without a ladder or allow it to grow to the proportions of a full sized fruit tree .

To create a whip and tongue graft you match the thickness of a rootstock to the scion wood, make diagonal cuts and grooves in each, and the lash the pieces together with grafting tape. It’s not quite as easy as it may sound and takes a little practice to get the technique just right.

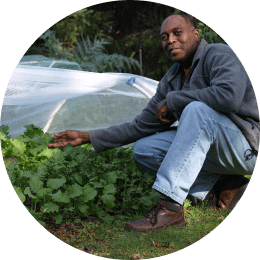

While even experienced fruit growers don’t achieve 100% success with their attempts at getting grafts to take and grow, youngsters like Olivia pictured above prove that grafting can become child’s play with a little care and practice.

For my time and effort I left the grafting workshop carrying six heirloom apple trees. Two Esopus Spitzenbergs, an Ashmead’s Kernel, a Caville Blanc d’Hiver, and two Yellow Newton Pippens, all grafted onto dwarfing rootstocks. My ultimate goal is to train the trees into a simple tiered espaliered shape, but the first I’ll have to cross my fingers and wait and see if the grafts will even take.

6 Responses

I have tried to graft Avocados and I have not had any luck at all. I live in California. Winter low 30’s – Summer high 100’s.

I love this site maybe I wanna create some later

I love this site maybe I wanna create some later